Don’t get me wrong, I love images from The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings but, truth be told, I have a soft spot for the charm of The Hobbit and its ability to accept so many varied interpretations over the weightiness of The Lord of the Rings. That said, many of my artist friends tend to prefer the drama and depth of world-building within The Lord of the Rings.

So, I put the question to them: which do you prefer working with and why?

For me, The Lord of the Rings will always be the overall favourite source of artistic inspiration, simply by virtue of its incomparable scope and depth. Among other things, it references the other two masterworks by Tolkien, The Hobbit and The Silmarillion, reinforcing its central place in the Middle-Earth canon. Arguably it also combines the best aspects of both—the great sense of epic forces, peoples and history, but seen from the point of view of a humble, endearing band of hobbits. Even though Tolkien changed passages in The Hobbit (particularly where the Ring is concerned) to better harmonize it with LotR, it doesn’t refer to its great sequel simply because Tolkien didn’t yet know he would write it. And since The Silmarillion was, to Tolkien in his lifetime, mostly a private source of backcloth lore (to vastly understate it), and is set so far back in Middle-Earth’s history, it can, by and large, be appreciated without needing to refer to the events of the time in which LotR or The Hobbit are set. Certainly no hobbits are involved whatsoever.

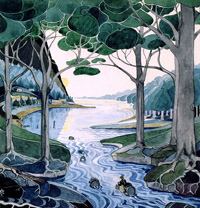

But I digress. As an artist who delights in traditions of panoramic landscape, and having been fueled by heroic adventure stories (particularly on film), The Lord of the Rings was bound to be highly suggestive as a vehicle for my artistic expression. That said, I’m sure glad it’s never been necessary to actually choose against either The Hobbit or The Silmarillion (or Unfinished Tales, Smith of Wootton Major, or any other rich narrative of Tolkien’s), since the former has long charmed me intensely, and is currently a renewed source of inspiration, while the latter got under my skin in the 1990s and hasn’t loosened its grip since. Both books, with their less elaborate styles of description (for different purposes) end up allowing greater participation for the artist in fleshing out images, since more room for imagination is available.

Interestingly, in the case of The Hobbit, we have Tolkien’s published illustrations to consider, too. Without wishing to draw anyone’s fire, and as charming as they are, they tend to suggest a simpler story than they in fact illustrate, given their stylized, naive look—and Tolkien was capable of more realism and detail if he put his mind to it, we know. For me, this is another facet of the pleasure in illustrating the book, since his artwork, being the author, contributes to a “feel” the book establishes for we readers, and presents a somewhat intriguing template to build upon, as I see it.

Between The Lord of the Rings novels and The Hobbit, I find images based on The Hobbit a little more interesting to draw. This is mainly because I like drawing monsters, and enjoy drawing monsters who have recognizable human personalities even more.

The trolls that argued over whether to cook the dwarves or squash them into jelly are more interesting than the trolls who assaulted the walls of Gondor with the armies of Mordor. The reason is because the trolls in The Lord of the Rings are the faceless, impersonal menace of the enemy. They are more like symbols of evil than actual characters with distinct personalities. And while I do love to draw images of epic battles between good and evil (what self respecting fantasy artist doesn’t?) and while The Lord of the Rings is a fountain of opportunities for this, I tend to find that there is a little more depth to the personalities of the monsters in The Hobbit. And so they make for more visually interesting characters to depict.

I think the reason that the monsters in The Hobbit have more personality is due largely to the narration. Tolkien chose for The Hobbit to be told by a charming (if not altogether reliable) individual in Bilbo Baggins, who tells the story as if to a nephew. Because of this much of the records of the events are imprinted by his own personality and so take on more of a personal character than they would have if this were a historical document. This in turn leaves the artist a lot of room for interpretation, which I think is one of the great strengths of this story for an artist. Tolkien himself acknowledges this unreliability in the narration of The Hobbit in later editions by actually blaming inconsistencies in the previous versions of the story on his narrator.

The Lord of the Rings, however, is less a charming fairy tale and more of an epic myth. And this is in part due to the narration changing from the somewhat subjective viewpoint of Bilbo to what feels like a group of poet historians who are writing a record of events that have been verified. This gives it the sense of being a cross between a record of the adventures of European knights in the crusades (which is terrifying literature) and of the prophetic poems of William Blake. Because of this, the monsters in The Lord of the Rings lose some of the individuality and personality that they had in The Hobbit, and they do this I think so as not to distract from the overall more epic mythological tone of the story.

This is not to diminish the monsters from The Lord of the Rings. They are some of the best that have ever been conceived and many will continue to be the icons by which all other contemporary fantasy creatures must be judged. It is just to say that I like drawing monsters that are just a little bit human, and who have personalities that you might recognize in people you’ve encountered in your own adventures, and The Hobbit has the very best of these.

I’m often asked to comment on this image, and usually reply that I tried to convey the impatient and reluctant road of the unwelcome messenger. That the tree and leaves are drawn into the wake of Gandalf’s hurrying, that the sunlit hills are a metaphor of untroubled times always eluding him, always a detour he has no time to make. That I tried to convey the weight of his cloak, the hem soaked in mud and dew, and the path fleeing under his feet. That I was thinking of all the grey pilgrims of myth when I painted this, of Odin and of the Endless Road. Of Mitharandir and Stormcrow and the power and duties of those who have many names. But all I am really thinking is that I wish I had drawn his outstretched hand a little better.

The Hobbit appeals to me more than The Lord of the Rings for a lot of reasons, but I think the primary issues are of scope and detail. LotR is absolutely Tolkien’s biggest literary achievement, but I’ve always thought the story gets bogged down by the details and the language. The Hobbit is a much easier pill to swallow in this regard: chapters are each headlined by a singular important event, and we’re given just enough description to fire our imaginations. The consequences of the quest are lesser than in LotR, and our narrator more charming. Bilbo tells his story like any grandpa would, and he only knows as much as he sees and is told. Bilbo doesn’t know the origin of the Goblins or how the spiders of Mirkwood are the daughters of Ungoliant or how Gollum came to live in the cave below the Misty Mountains. That information is all out there if we seek it, but it’s not what Bilbo’s story is about. Tolkien and Bilbo let us interpret the ins and outs of Middle-Earth however we want, and so the story is easier to deal with. There’s no dark lord to foil, and no burden to bear beyond our limitations. The world isn’t ending, it’s just that some dwarves want their stuff back.

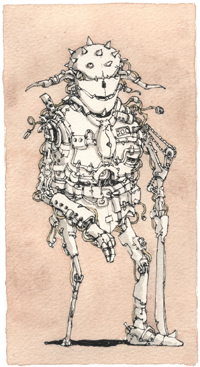

My favorite is The Lord of the Rings. Reading The Hobbit now, I find it more of a sketch, more like a children’s book, and I find that children’s books have more of a tendency to age. To be frank, I find it hard to Illustrate Tolkien’s work; the words are more than enough for me, that’s probably why I choose to make the characters into robots.

As far as my favorite, The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings, I would have to say the latter—for me it is a question of the author’s maturity as an author. The Hobbit is first and foremost a children’s book, while the Trilogy is an all-ages story. It uses the same characters, but look at how vastly more realized these characters are, and the Elves are the most dramatic example of this: the Elves in The Hobbit are stock fantasy characters, while in LotR they are the most powerful and mysterious and beautiful of all the inhabitants of Middle-Earth. Or the Dwarves—that repeated litany of names, always in the same order, makes me hear voices (especially in the recorded version—well, you get the idea).

The main reason for this is, of course, that The Lord of the Rings has a half-million year back-story behind it, in the form of The Silmarillion, a classic example of how a well thought-out back-story can turn a simple tale into a luminous epic fantasy. Both of these stories have their appeal—the charm factor of The Hobbit is undeniable. But the amazing development of that story into the Trilogy leads to more pictorial ideas if only because of the length [though admittedly, LotR doesn’t have any dragons in it…]. And because the characters have evolved, there are more enduring favorites in the Trilogy than Gandalf and Bilbo.

One’s memory of The Shire and its familiar landscapes, people and essence, gleaned from reading The Hobbit, is found to have been enhanced into that well-known, comfortable place from one’s having read The Lord of the Rings. Bag End, Hobbiton and even more so The Shire, are merely touched on in the earlier story. Without benefit of the time spent in The Shire during the first few chapters of The Fellowship of the Ring, The Shire in The Hobbit is bounded by the walls of Bag End, with a brief glimpse of the path leading up to Bilbo’s front door, and a nighttime sprint through the bottom field.

It’d be impossible for me to draw a scene from The Hobbit without relying heavily on the imagery, stories and sensibilities that are so finely delineated inside The Lord of the Rings.

Back in 1976-77, when Steve Hickman and I were hoping to get to draw and paint the 1979 or 1980 JRR Tolkien Calendar, we mapped out a good sampling of the High Points of The Lord of the Rings, touching on as many of the dramatic scenes as we could hope to have (14 at the time: back then the cover used to be a separate image from the body of the calendar, and there used to be a stand-alone center spread). As we happily indulged in the mystery, awesome beauty, and warfare that abounds in the Trilogy, it came to us that we had covered all the Dark energy of the books without once touching on the Light. There was a bit of a flurry of pages, paper, and pencil while we sacrificed several of our strong iconic choices and levered in some of the sunlit happiness everyone remembers when thinking back on The Shire. Just as Frodo, Merry and Pippin must have felt in their hearts on their homeward journey, we knew The Shire represented Home, Peace, Safety, Relaxation and Comfort.

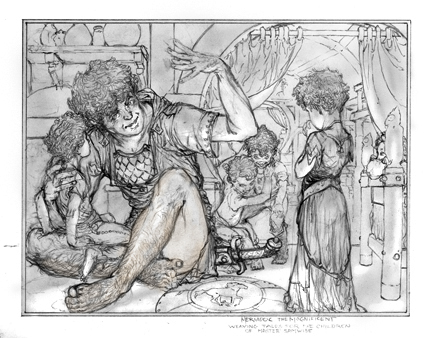

Finding a first Shire image was easy—Gandalf arriving in Hobbiton with his cart of fireworks—but at the end of the tale, where was the happiness unmixed with loss? Well, we found it in The Appendices, not exactly described, but there all the same. The December image proposed for the never-produced earlier project (ultimately finished for my solo 1994 JRR Tolkien Calendar), was Meriadoc The Magnificent, the tallest Hobbit as ever was, telling the story of the descent of the Witch-King of Angmar at the Battle of the Pelennor Fields to Sam’s children. Little Merry and Little Pippin, having heard the story before, are each daring the other to touch Merry’s dagger, little Frodo-lad sits fascinated on Merry’s knee, while the youngest, Goldilocks, hides behind a pillow on the bed, still needing to watch. Eleanor, totally in love, stands listening to other words in her secret heart.

![]()

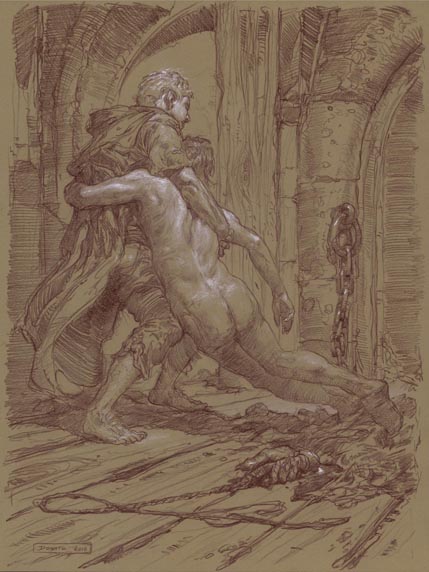

For me there is no contest: The Lord of the Rings provides the richest characters, dramas and humanistic challenges in comparison to The Hobbit. The burden of the quest to unmake the Ring provides the gravitas I love to mine when creating images from Middle-Earth. Rather than depict the epic and momentous confrontations which abound in both books, I have been exploring how to illuminate the fleeting moments which reveal the compassion and humanity of each character. The numerous personalities in The Lord of the Rings provides me with page after page of inspiration for my paintings and drawings. In celebration of these artworks, a new book of my Tolkien visions is due out this fall from Underwood Books: Middle-Earth: Visions of a Modern Myth.

![]()

I was introduced to Tolkien’s work in the early sixties. I read The Hobbit first, quickly followed by The Adventures of Tom Bombadil. This of course lead on to The Lord of the Rings. I was also reading the Gormenghast trilogy by Mervyn Peake at that time, which provided a superb visual counterpoint to Middle-Earth. It was was a seminal period in my life.

In the mid-seventies I was commissioned by the publisher Mitchell Beazley to work on the Tolkien Bestiary by the writer David Day. This provided me with the wonderful opportunity to express my feelings about Tolkien’s world in picture form, and for the most part my images were well received.

Because we now live, at least in the developed world, in a place that to all intent and purposes is permanently lit, it is perhaps difficult to really grasp or understand just how frightening the dark must have once been with nothing beyond the flicker of a night torch but the quiet tread of hungry wolves, and a disparate assortment of malign spirits intent on harm.

Tolkien was very much influenced by Beowulf and in his own epic he clearly underscores the harsh, sometimes primeval, struggle between light and dark. The happy disposition of the hobbits, their vulnerability and the mysterious light of the elves, is always more real for me when set against the sharp teeth of something dark and predatory.

This vital counterpoint is something I always look for and try hard to emphasis in my own work. The dwarves, goblins and orcs are gainsaid.

Plenty of other artists have taken Tolkien on—Alan Lee, of course, Tove Jansson, the Hildebrandts, and countless others—please add to the list and talk about your favorites.

Irene Gallo is the creative director of Tor.com and art director of Tor Books.